This Language Is Never Complete

(ft. Natalie Wee)

December 1, 2020

Teh Talks is a series of exploratory conversations between creatives.

This conversation between Jasmine Gui (@jaziimun) and Natalie Wee (@revengerice) has been scrambled and edited with love.

My origin story with Natalie begins with a serendipitous meeting at a bookstore that I walk into on a whim. It’s a temporary pop-up; a zine in the window catches my eye; Natalie is working behind the cash that day. It’s the wet dream of literary aficionados and romantics everywhere. But the years that follow are not a rose-coloured montage of a beautiful life. They are, in fact, mostly a slow growing journey, hard conversations repeated over and over, fractures and repairs, and lots of talking about writing, writing about writing, revising writing, and writing.

Do you have anecdotes about your early writing attempts?

My early writing attempts

were unhealthy and largely characterized by anxiety. I used to hinge my

identity very strongly on only being a writer, and so I placed an

incredible amount of pressure on anything I wrote. I’d engage in a lot

of negative self-talk, worry about the reception of my work, and berate

myself for failing to be “inspired.” This fixation with constantly

creating or knowing the right people was incredibly poisonous not only

to my ability to write but also my sense of self-worth. Ironically, it

wasn’t until I stopped thinking of myself solely as a writer that I

managed to develop a healthier relationship to writing.

Trace a lineage of writers. Who are your biggest influences?

Hanif Abdurraqib is a writer I admire endlessly and the first poet I was very curious about. The ingenious way he uses pop culture as entry points to bring readers into experiences really introduced me to the idea that almost anything can be a doorway. It’s also no secret that Ocean Vuong is currently my greatest influence and has been for a long while. Ocean’s work was my first exposure to other LGBTQ+ South-East Asian folks writing poetry in english, and that sensation of being seen allowed me ultimately to create my own work with courage.

I find myself consistently enraptured by the work of Danez Smith, Fatimah Asghar, Ada Limón, Hieu Minh Nguyen, Jericho Brown, Leila Chatti, Franny Choi, Joy Harjo, Toni Morrison, and Layli Long Soldier.

At this moment, contemporaries I deeply admire include Sanna Wani, Whitney French, Laetitia Keok, Brandon Wint, Aseja Dava, Nshira Turkson, Yves Olade, Arielle Twist, Kai Cheng Thom, Alicia Elliot, Manahil Bandukwala, Christina Im, Lamia Akbar, Syan Jay, Beni Xiao, Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch, Rebecca Salazar Leon, Cason Sharpe, Nisha Patel, Marcela Huerta, and Alex Dang!

Uncoupling #1

The process of uncoupling was one of resurfacing from a river. I have a background in performance arts, and before I pursued writing seriously, I had actually considered working in film or theatre. It’s ironic that I had initially just tried my hand at writing without any formal training, but was terrified of trying something new and being mediocre at it. It didn’t help that most writers in the “CanLit” literary scene were hyper-focused on writing made me feel like I’d be diverting my attention or wasting time by trying something else, especially as it felt like I was constantly playing catch-up without the technical skills or associations that came with an MFA.

How has your relationship to language changed over time?

In an interview, Vuong talked about the casual violence often employed in speech in America. “You killed it.” “I knocked it out of the park. I went in there, guns blazing. Go knock ‘em dead. Drop dead gorgeous.” Language is, as he pointed out, an embodied craft. There are many conventions in the language that I’m working to unlearn. I must ask myself constantly what it means to write in english—the language of those who colonized the land where my parents were born, the land where I was born, and the land where I later chose to settle. How can I work against the colonial ideas already embedded in this language, both in writing and in my everyday life? As a multilingual person in diaspora, writing in english also means being aware of its failures: one of my favourite words in Bahasa Melayu, “sayang,” is a noun, verb, and phrase depending on context. Translated, I could say that its english equivalent is “darling,” “beloved,” but carries none of the emotional gravitas built into a word that also means, “[it’s] a pity.” Thus writing in english is a constant act of approximation for someone who has lived in more than one language; my writing in this language is never complete.

Do you have any rituals for when you write?

Often I write the same sentence over and over until it transforms into something that surprises me. I visit discarded sentences from the past and try to resurrect and reinvent them. I often write on scrap material like receipts and napkins before transferring phrases to a notepad, and then to a word doc for a final edit. This practice builds courage for me to experiment with language and make mistakes.

Send me a song you listen to when you write.

Things began changing during the time I spent as part of Project 40, the Asian Canadian art collective. I met many interdisciplinary artists, and moved away from purely literary events into events that incorporated music, poetry, fiction, video work, and much more. Even then, I kept rationalizing to myself that multidisciplinary artists had what I didn’t: training, skills, talent.

Uncoupling #2

During the time when I was at an all-time low with my writing, it was actually you, Jasmine, who told me, “You’re worthy of love even if you never wrote a single word again in your life.”

And that really shook me.

Ultimately this book project met with unforeseen circumstances, and Natalie pulled the manuscript from publication production. Regardless, it was a labour of immense trust and love.

What was it like to take the older Our Bodies And Other Fine Machines and rebuild it for this season?

The process was both an excavation and burial. I did not initially believe this collection needed to be reprinted, because it was the product of a poetic voice that I had long outgrown, and therefore a speaker that no longer exists. I had to hold each poem up to the light and ask myself if it had enough transformative potential to be worth salvaging. I imagined standing at the threshold of a new era, asking: What can I carry forward, and what must I kill? Deciding which of my newer works to add to the collection involved threading through my past and present voices, and imagining the experience of a new reader on this journey. The end product—this second iteration—is a bridge.

What was the first collection about, and has the second edition shifted in focus and interest?

We discussed writing as different snapshots of our creative journeys,

which is an apt metaphor in discussing the two iterations. The first

edition was written at a time when I was still trying to develop a

poetic voice, and I think the writing tells on itself in possessing huge

optimism even as it fails to arrive at what it reaches for. It was in

many ways a plea, a demand for affirmation and validation from a speaker

who asks to be understood.

This second iteration emerges out of a relationship with language that has evolved to a certain degree of comfort and ease with writing about difficult topics. I am now able to create a speaker that is unrepentant and unapologetic in experimenting, who no longer has to write herself into existence for an imagined audience.

All this to say, the first edition sounded like, “Please look at me,” while the second edition sounds more like, “I’m here. Look.”

Why did you pick fiction to tell your next story?

Before I could read in any language, I grew up with my grandmother’s recollections as my first true creation stories. Her voice in my ear sketched out history more powerful and absolute than any mythos. Beyond the gift of trust, I believe she shared these stories to remind me that I am an embodiment of history I cannot touch—and as I struggled with suicidal ideation for over a decade, this reminder is what constantly saves my life, and the foundation of my preoccupation with stories. What are the narratives we tell ourselves to stay alive a little longer? What does the truth matter if you want to live? Where does the account begin and who’s telling it? I’m interested in what happens when we leave these possibilities in a room together. I think what emerges is amorphous but understood as poetry or fiction based on evolving customs of genre—I’m fascinated by prose poems and novels in verse.

I’m not sure what I’m writing is fiction besides the fact that it’s a reinterpretation of a creation story and there are multiple characters in there. I’m hoping to find out and I hope you’ll join me.

![]()

Writing is an endless process of starts and stops, of attempts and failures, and very occasional successes. If you give up when you find yourself standing in your own way, then you might really never write again. To me, this is not necessarily devastating. I am suspicious of the exceptionalism used to package writing or any kind of creative pursuit. This might sound strange coming from someone who so recklessly and lovingly pursues art in her life, but the only exceptional thing for me is to have existed at all, no other conditions. This rings even truer for me, for those whose lineages and histories and genealogies are of survival against violent erasure. In my ongoing journey with Natalie, I celebrate the exceptionalism of her existence, and then, I also love her words.

IN FACT, I love them so much that Teh People has decided to personally take on the task of producing a special edition of Our Bodies And Other Fine Machines for a 2021 summer release under the newly launched San micro press.

May this specific genealogy exist well and safely, for those who may need it, and for those who have journeyed with us so far.

![]()

Photograph a place where you think a lot about writing.

![]()

![]()

This second iteration emerges out of a relationship with language that has evolved to a certain degree of comfort and ease with writing about difficult topics. I am now able to create a speaker that is unrepentant and unapologetic in experimenting, who no longer has to write herself into existence for an imagined audience.

All this to say, the first edition sounded like, “Please look at me,” while the second edition sounds more like, “I’m here. Look.”

Uncoupling #3

It

became quite apparent I had completely internalized the capitalist

belief that I was only worthy if I could produce something I was good

at. I had not considered that I didn’t have to earn my place in the

world, or my right to create art. I started asking myself:

Will this next sentence add anything to my life?

Whom do I owe my writing and what does my writing owe me?

Once I considered how much of my relationship to my own writing was about a fear of being discarded, it was easier to reframe my anxieties. I’m fortunate enough to be surrounded by incredible, life-changing friendships and community, and the knowledge that I’d be loved even if I fail gives me courage to continue.

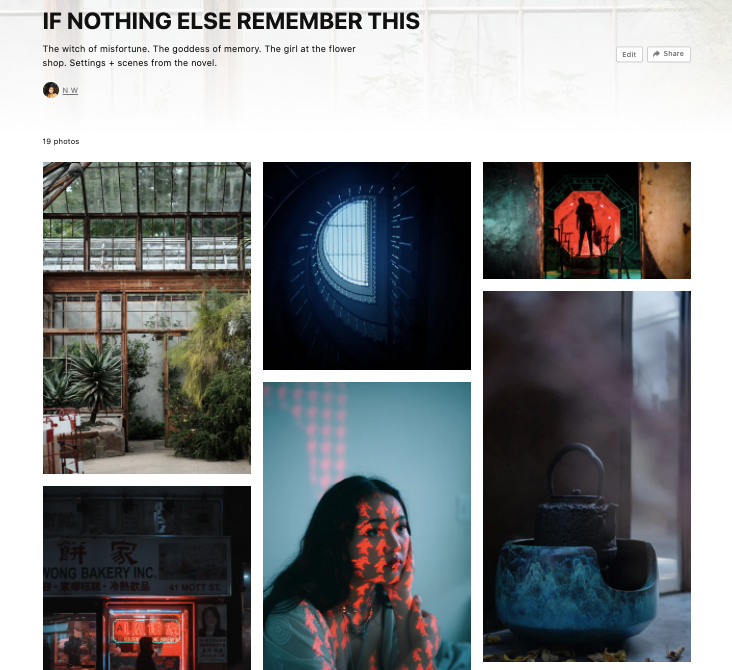

Mood Board for current manuscript:

![]()

Unlike poetry, where I’m typically only crafting one speaker at a

time, the fiction I’m working on requires multiple speakers inhabiting

the same narrative space, interacting with each other. That’s definitely

something I struggled with, alongside plotting. I do not often plan my

poetry; sometimes I begin with a phrase and the rest of the poem

arrives. For fiction, though, my approach is more deliberate. It’s not

enough to move forward with just an image, because demanding sustained

engagement necessitates substance. Because I’m new to writing fiction,

this has been a process of experimentation. When I first started working

on this in 2016, the story was set in a high-powered spaceship and

dealt with sci-fi themes, but since late 2018 this setting has shifted

to modern-day west Chinatown in Tkaronto and draws more on fabulism.

Likewise the characters’ motivations and backstories have changed to

reflect the new themes pushing the plot forward.Will this next sentence add anything to my life?

Whom do I owe my writing and what does my writing owe me?

Once I considered how much of my relationship to my own writing was about a fear of being discarded, it was easier to reframe my anxieties. I’m fortunate enough to be surrounded by incredible, life-changing friendships and community, and the knowledge that I’d be loved even if I fail gives me courage to continue.

Mood Board for current manuscript:

You’re also writing fiction right now. What are the biggest differences in how you approach each genre?

Why did you pick fiction to tell your next story?

Before I could read in any language, I grew up with my grandmother’s recollections as my first true creation stories. Her voice in my ear sketched out history more powerful and absolute than any mythos. Beyond the gift of trust, I believe she shared these stories to remind me that I am an embodiment of history I cannot touch—and as I struggled with suicidal ideation for over a decade, this reminder is what constantly saves my life, and the foundation of my preoccupation with stories. What are the narratives we tell ourselves to stay alive a little longer? What does the truth matter if you want to live? Where does the account begin and who’s telling it? I’m interested in what happens when we leave these possibilities in a room together. I think what emerges is amorphous but understood as poetry or fiction based on evolving customs of genre—I’m fascinated by prose poems and novels in verse.

I’m not sure what I’m writing is fiction besides the fact that it’s a reinterpretation of a creation story and there are multiple characters in there. I’m hoping to find out and I hope you’ll join me.

Writing is an endless process of starts and stops, of attempts and failures, and very occasional successes. If you give up when you find yourself standing in your own way, then you might really never write again. To me, this is not necessarily devastating. I am suspicious of the exceptionalism used to package writing or any kind of creative pursuit. This might sound strange coming from someone who so recklessly and lovingly pursues art in her life, but the only exceptional thing for me is to have existed at all, no other conditions. This rings even truer for me, for those whose lineages and histories and genealogies are of survival against violent erasure. In my ongoing journey with Natalie, I celebrate the exceptionalism of her existence, and then, I also love her words.

IN FACT, I love them so much that Teh People has decided to personally take on the task of producing a special edition of Our Bodies And Other Fine Machines for a 2021 summer release under the newly launched San micro press.

May this specific genealogy exist well and safely, for those who may need it, and for those who have journeyed with us so far.

Photograph a place where you think a lot about writing.

If you could show (not tell) your younger writing self something, what would it be?

I’d show her my camera roll: all the selfies with friends and indecipherable inside jokes. (Is this cheating if I’m showing her more than one thing?) That younger writing self is an ancestor trying to build her way into worthiness, into existence. I want her to gift her snapshots of the life surrounded by tenderness and joy, to show her that creating does not always have to be grief work and moving with the urgency of a surgeon’s scalpel. Writing is only one form of existing. We can always live in the world while trying to invent kinder ones.